A note on language: when there is an international or English-language name in common use, that will be used. The version of the name in the individual’s modern local vernacular will follow with the two-letter language code.

For further reading: not much English-language scholarship has been given to the Royalist supporters of Philip II. For those interested in their roles, actions, and influence, the best accounts will be general histories of the conflict, which you can view as part of the larger Renaissance Netherlands research bibliography here.

Contents

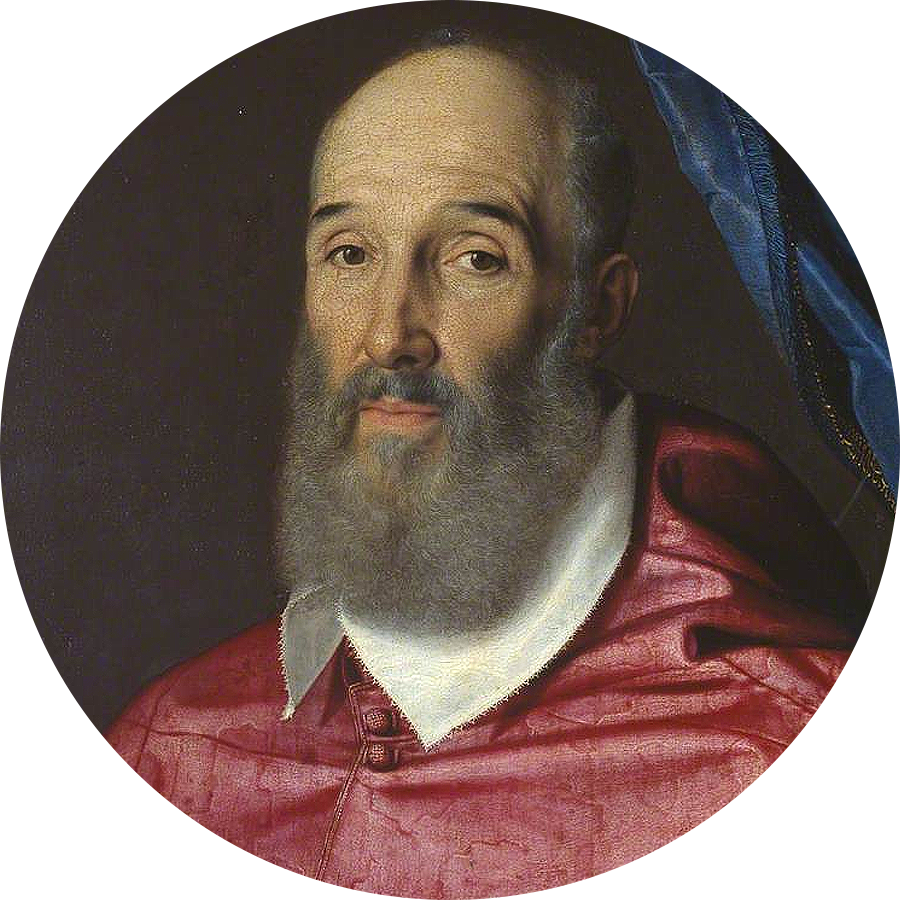

Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, Archbishop of Mechelen

1517-1586: His father was a well-connected and influential advisor to Charles V, and so it was nearly expected for Granvelle to assume a similar place of influence with Charles’ son Philip II. When the king departed the Low Countries in 1559, Granvelle was appointed chief advisor to Margret of Parma, Phillip’s sister and governor-general of the Netherlands.

In this role, he would push for strongly Royalist and Catholic policies which antagonized the local nobility and provincial governments. As a result, he became the figure of much vitriol and protest, which would in turn force his departure from the Low Countries in 1564.

Philip de Croÿ, Duke of Aerschot

1526-1595: One of the most powerful nobles in the Low Countries and political rival to William the Silent, Aerschot had a long, complicated, and convoluted relationship with the Dutch Revolt.

A devout Catholic, Croÿ did not support the removal of Granvelle from office, but nonetheless supported the initial rebellion – going so far to entice a young Archduke Matthias of Austria to come serve as governor (as a counterweight to William the Silent). Later, he would reconcile with Philip II, only to ultimately clash with the king one last time in 1594, when he refused to serve under a new governor. He would retire to Venice and die a year later.

Peter Ernst von Mansfeld

1517-1604: A German nobleman born to a family well-connected to the Habsurgs, Mansfeld served both Charles V and Philip II as a soldier and as governor of Luxembourg for nearly fifty years. When the Dutch Revolt broke out, Mansfeld remained loyal to the king and lead troops under both John of Austria and the Duke of Parma – even serving as interim governor of the Royalist provinces after the latter’s death.

Such long and loyal service did not result in riches and fortune. In fact, it was quite the opposite. The cost of raising so many troops through his long career was enormously expensive, and he and his brothers’ estates in German lands were confiscated in 1579 to settle his debts. Though he built a stately castle home in Clausen, Luxembourg – complete with fine gardens and antiquities – he was essentially bankrupt when he passed in 1604.

George van Lalaing, Count of Rennenberg

1550-1581: Rennenberg was a member of a powerful noble family from Hainaut. But where most of the Catholic nobles in the southern provinces – including his own family – remained loyal to the king, Renneberg was one of the few to pledge his support to the incipent rebellion. In 1577, he was appointed stadtholder of the northern provinces of Friesland, Groningen, and Drenthe by the rebellious States General.

When the rebellion shifted from religious peace to favoring the bellicose Calvinist faction, Rennenberg declared himself in favor of Philip II. This “betrayal” further added to the religious polarization of the war and marked a turning point for Catholics being trusted with positions of great importance by the Dutch.

Emanuel Philibert van Lalaing, Baron of Montigny

1557-1590: Another member of the vast Lalaing family, Montigny was cousin to Rennenberg – and also paralleled his kinsman’s career and thinking, but much more successfully.

As the Calvinists gained power, Montigny lead the Catholic “Malcontents” in negotiations with the provincial estates of Hainaut (whose stadtholder was Emanuel’s half-brother Philipe), Artois, and other cities – as well as with the Spanish under Parma. This would result in the 1579 Union (and later, Treaty) of Arras, which would decisively sever the northern and southern provinces. Montigny would go on commanding troops until being mortally wounded in the 1590 Siege of Mons.

Charles de Croÿ, Duke of Aarschot

1560-1612: Son of Philip, the younger Croÿ followed in his father’s footsteps as both soldier and government official, first as a seventeen-year old officer in his father’s Waloon regiment. In navigating the complexities of the shifting, evolving political situation, he continued in service to the Dutch rebels until 1584, when he seperated from his strictly Calvinist wife, returned to the Catholic church, and reconciled himself to the king by way of the Duke of Parma.

He would go on to lead troops for the Habsburgs in both the Low Countries and France for the next several decades while maintaining his lands in the south – lands which have been documented and illustrated in a series of pictorial albums.

The Dutch Revolt which began in 1568 is not as simple as the story of one nobleman rebelling against the King of Spain. There were supporters and partisans on both sides of the conflict enabling – and often forcing the hand of – that one noble house and their Habsburg overlords.

Back to Leaders, Soldiers, & Politicians from the Dutch Revolt